Writer Alison Wormell takes us on an exploration of the music of our Florescence program which tours Australia between July—November.

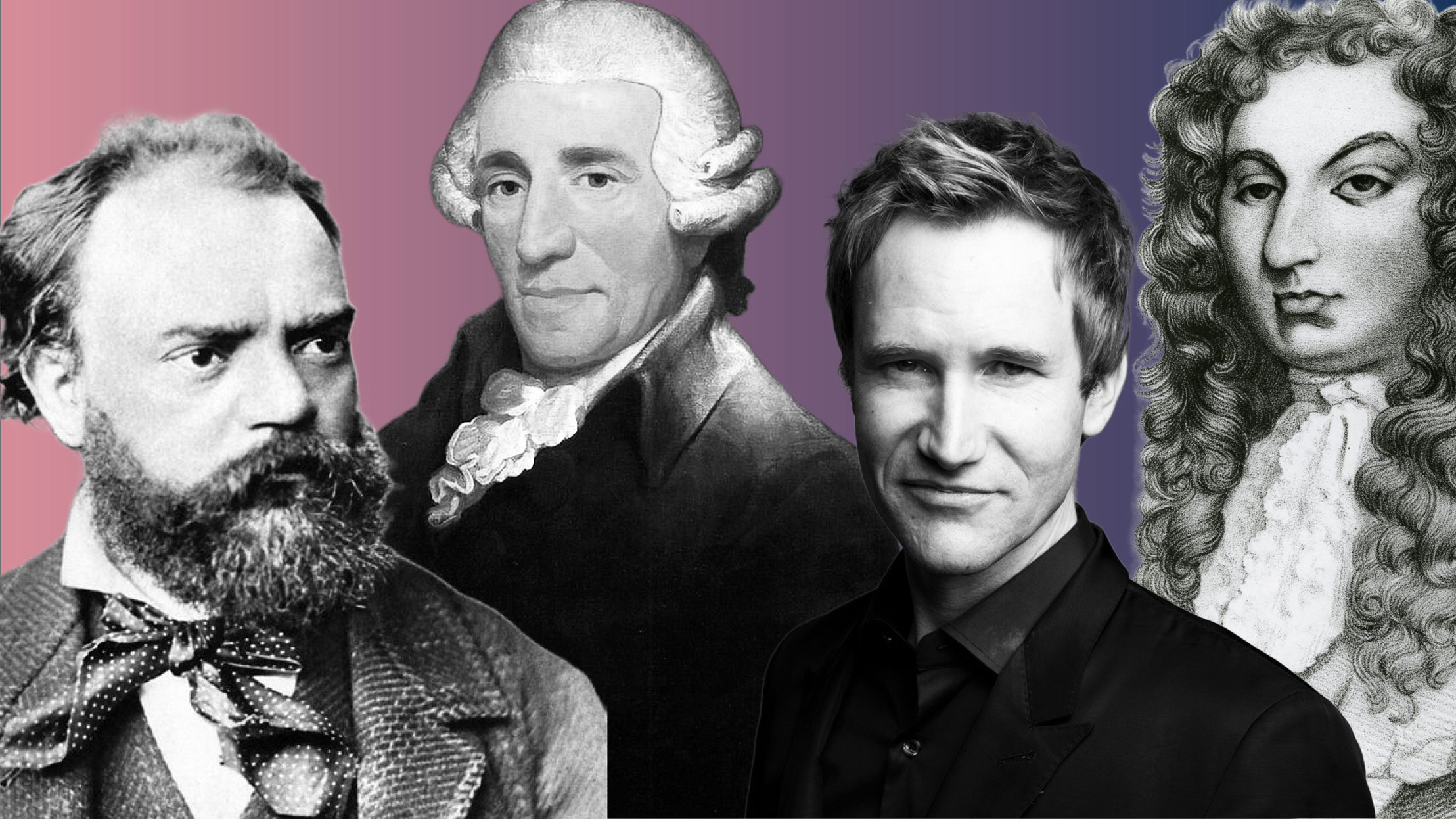

David Attenborough made television history when he presented time-lapses of plants growing and flowers unfurling in his 1995 documentary The Private Life of Plants. In this concert, the Australian String Quartet embarks on their own deep dive into ‘florescence’; the process of flowering or fully developing. The music ranges from a proto-string quartet by Purcell, via Haydn and Dvořák, to Justin Williams’s pandemic offering. Together we will explore different moments of blossoming in the composers’ careers, their historical significance and creative voices.

The first work is Movement for String Quartet (2020) by Australian violist and composer Justin Williams. Completed at a time when public performances weren’t permitted, this piece is his first serious attempt at composing. Williams has drawn on his personal experience as a member of the Tinalley String Quartet to produce a gripping work that oscillates between tortured, ecstatic and delicate.

From the very first flourish, the listener is thrust into a dark, uncertain world. The grating interval of a tritone – the halfway point in an octave also known as ‘the devil’s interval’ – is used extensively here. Eventually, a lone violin calls out and seems to calm the storm. Movement for String Quartet is full of contrasting moments like these. The four players will sound like they are duelling then instantaneously switch to playing the same rhythm as a unified ensemble. Expect tense chordal moments that sound as rich as a symphony orchestra, brief moments of stunning clarity and cheeky conversations that devolve into ecstatic dances.

The second work you’ll hear is Franz Joseph Haydn’s String Quartet in B minor, one of six quartets that the Austrian composer published in 1781. If you came to Utopias earlier in the year, this is one of the quartets that inspired Mozart to write his String Quartet No.15 in D minor which was presented in that concert.

Haydn is often referred to as the father of the modern string quartet due to his work in developing the genre. This quartet was published after a ten year break in composing for the combination. It’s full of easy confidence and there’s an abundance of positivity throughout, despite being in a melancholic key. Overall, it’s simply more humorous than Haydn’s earlier quartets. This piece is an example of the string quartet flourishing under Haydn’s care as he returns to the genre after years focusing on opera productions.

The first movement is unusual as it only has one melody or ‘theme’ instead of the traditional two. This melody starts with a descending run which you should listen out for. Haydn is endlessly inventive and it’s interesting to hear him play with such a simple theme across this movement. The second movement is joyful despite being in a minor key. The scherzo title implies humour and there’s certainly a joke happening as question and answer phrases are thrown around the ensemble.

Conversely, the third movement evokes a stately dance, in D major. The slowest movement in the quartet, it maintains an easy tempo throughout. The cello and first violin exchange dialogue in this one; is it flirtatious or serious? Not one to leave the listener dissatisfied, Haydn brings us to an exciting finish with a wild and fast Finale!

Fantasia No.6 (1680) by British composer Henry Purcell predates the string quartet as we know it. It was written when people wrote for consorts which were ensembles made up of the same instrument in different sizes. Purcell’s fantasias range from needing three to seven viols (predecessors of today’s string instruments) – this one requires four players.

This fantasia uses lots of different melody lines to create counterpoint similar to the English vocal music of Purcell’s time. In the two fast sections, listen to the very first few notes the violin plays, then try to spot them as they appear over and over again, oscillating almost hypnotically. In the two slow sections the parts wind around one another in slow motion, grinding and crunching against each other, gradually moving toward a peaceful resolution.

The concert finishes with Antonín Dvořák’s String Quartet No.14 in A-flat Major (1895). Dvořák is best known for his symphonies and tone poems, using Czech folk music even when he had spent several years working in New York. This is Dvořák’s final string quartet and his last work for ensemble without an underlying story or program. Written two years after the famous New World Symphony, this is Dvořák in bloom, full flower.

The work starts atmospherically with solo cello, the performers mimicking each other before diving into a happy main theme. This mood continues into the second theme which is more fanfare-like and pits the players in fun dialogue against each other. There are a lot of these exchanges throughout the piece where independent melodies come together in harmony.

A hiccuping melody opens the second movement, turning gritty with the stamping of folk dancers embedded in the music. A middle section is more lyrical and introspective, providing contrast, before we hear the dance music again. Dvořák’s lyricism returns in the intimate third movement as the first violin plays a melody drenched in warm fondness. There is a gradual build in intensity to a passionate and fevered atmosphere, but the song-like characteristics remain throughout this movement.

The fourth and final movement is a rollicking romp, bickering exchanges interspersed with pastoral moments. Dvořák pulls out all the stops, speeding to a triumphant and spirited end!

© Alison Wormell 2023